"The Atom Bomb Dancers": Sexuality and the Bomb (August 6TH, 1945- ?)

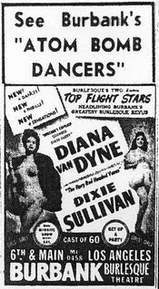

Although there has been a long standing association between female sexuality and destruction in different mythological stories, in the 20th century, common references to women, such as calling them “bombshells”, which had been around since the 1930s, took on even greater significance with the advent of the atomic bomb. The introduction of the atomic age seemed to immediately carry with it a heightened sense of sexuality, and in turn magnify the relationship between destructive and sexual forces. Only two days after the bombing of Hiroshima, on August 6th, 1945, the Burbank Burlesque Theatre in Los Angeles invited readers to come see the “Atom Bomb Dancers”. Just following the bombing of Hiroshima, and well before the second bombing of Nagasaki, the destructive potential of the bomb was immediately linked to displays of female sexuality in an almost celebratory manner.

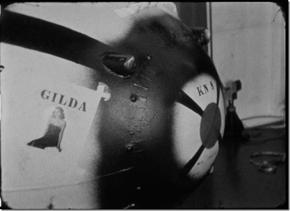

In addition to inspiring one of the most iconic swimsuits, the Bikini, Operation Crossroads further exemplifies the connection between sexual and destructive forces. Of the two bombs tested at the Bikini Islands, the ABLE test bomb had a picture of Rita Heyworth attached to it, and was named Gilda, after Heyworth’s character in the American black-and-white film noir of the same name. In the film, Gilda, the ultimate femme fatale, reiterates this connection between female sexuality and destructive power by singing “Put the Blame on Mame” (sung by Anita Ellis), which credits the amorous activities of a woman

|

|

named "Mame" as the actual cause of cataclysmic events in American history. This connection to Gilda, and not Rita, provides greater insight into this relationship -- harnessing both the power of the atom and the sexually destructive power personified by Gilda. During later tests in the Nevada desert in the 1950s, America became increasingly familiar with the atomic bomb, and its appeal began to grow even further. Nevada casinos capitalized on the “A-bomb” as a cultural phenomenon.

|

Lee Merlin "Miss Atomic Bomb"

Lee Merlin "Miss Atomic Bomb"

Combining the bomb with Las Vegas' well-known showgirls Nevada casinos created “Miss Atomic Bomb”. Over the years, there were several “Misses”: “Miss Atomic Blast”, “Miss A-Bomb”, and even a “Miss Cue” after the Operation Cue tests. The most famous photos, of Copa Showgirl Lee A. Merlin, taken by Don English shows Miss Atomic Bomb 1953 (Merlin) with a mushroom cloud made of cotton attached to the front of her swimsuit. (Other Misses donned mushroom cloud crowns while wearing what resembled their showgirl costumes). Despite the growing popularity of the atomic bomb, as the public began to learn about the actual devastation it had caused in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, fear began replacing the bomb’s appeal.

Following the testing of an atomic bomb by the Soviet Union, this sexual energy gave way to growing fears. Containment seemed to be the only strategy for avoiding nuclear war, and so too would sexuality need to be “contained”. The symbolic connection between sexual chaos and atomic attack found widespread expression. Americans’ concern with sexual-laxity paralleled their concerns of internal Soviet subversion, as a popular notion connected Communism with sexual depravity began to take root. Communists, who would stop at nothing to gain nuclear secrets, were thought to use any means, including sexual espionage, to sabotage the country’s stability. The result was the belief that the sexually weak or deviant posed an internal threat. Just as other forms of fear led to “red-baiting” and hearings over the “Un-American-ness” of activities, sexual activities were increasingly under suspicion and review. The search for “perversion” or “deviant” sexual activities led to the persecution of homosexuals through a form of “gay-baiting”. People who chose paths that did not include marriage and parenthood could also find themselves under suspicion. This pressure led many to marry early, and many to marry to the opposite sex despite their sexual orientation, in order to escape the stigma and persecution.

Following the testing of an atomic bomb by the Soviet Union, this sexual energy gave way to growing fears. Containment seemed to be the only strategy for avoiding nuclear war, and so too would sexuality need to be “contained”. The symbolic connection between sexual chaos and atomic attack found widespread expression. Americans’ concern with sexual-laxity paralleled their concerns of internal Soviet subversion, as a popular notion connected Communism with sexual depravity began to take root. Communists, who would stop at nothing to gain nuclear secrets, were thought to use any means, including sexual espionage, to sabotage the country’s stability. The result was the belief that the sexually weak or deviant posed an internal threat. Just as other forms of fear led to “red-baiting” and hearings over the “Un-American-ness” of activities, sexual activities were increasingly under suspicion and review. The search for “perversion” or “deviant” sexual activities led to the persecution of homosexuals through a form of “gay-baiting”. People who chose paths that did not include marriage and parenthood could also find themselves under suspicion. This pressure led many to marry early, and many to marry to the opposite sex despite their sexual orientation, in order to escape the stigma and persecution.

Resources:

May, Elaine Tyler. “Explosive Issues: Sex, Women, and the Bomb”. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books Inc. 2008.

May, Elaine Tyler. “Explosive Issues: Sex, Women, and the Bomb”. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books Inc. 2008.